Assessing potential flood damages in warmer, wetter Wisconsin

Since 1950, Wisconsin’s average daily temperature has increased by 1.6 C (3 F). The state’s average annual precipitation increased by 17 percent or about 13 cm (5 in) from 2010-2019 making it the wettest decade since 1900 when record-keeping began. Overall, the southern half of Wisconsin is seeing the largest increases in precipitation.

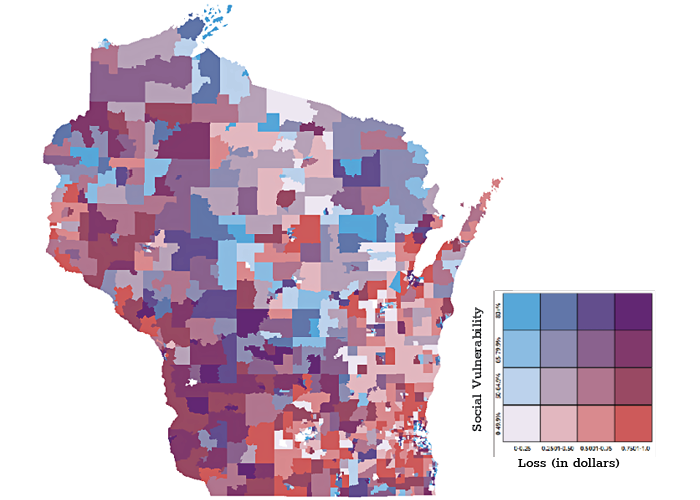

Credit: Shane Hubbard.

The relationship between atmospheric warming and precipitation is well understood: A warmer atmosphere can hold more water vapor which in turn can trigger more, and in some cases, heavier, rainfall and flooding.

“We have a changing climate with changing rainfall and these changes in precipitation, while they may seem insignificant, are amplifying the impact,” says Shane Hubbard, a researcher with the University of Wisconsin–Madison Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies. He says that we need to adjust to this new normal by changing our building practices.

Credit: Shane Hubbard

The increase is particularly apparent in places like Sauk County that has been ravaged by two major floods since 2008, both of which resulted in a Presidential Disaster Declaration. After the disastrous flood of 2018 that displaced people and businesses, the city of Rock Springs, situated near the Baraboo River, decided to move its downtown to higher ground and outside of the floodplain where it had been located for 140 years.

Hubbard has developed tools to help communities estimate damages to buildings if a flood were to occur in a certain area, like in or around designated floodplains along a stream or river.

Over the last year, he and a team of researchers from CIMSS and the POLIS Center at Indiana University gathered data on the locations of buildings in every county in Wisconsin that are at risk from a flood of a magnitude that statistically would occur once every 100 years or a 100-year flood. The group targeted buildings because the biggest financial losses come from water damage to built structures, including houses, and these data were readily available.

Any calculation about flooding must consider not just the volume of water, but where that water will drain. The growing number of impervious surfaces in cities, like parking lots, streets and buildings, are adding to the drainage problem as are farming practices such as tilling that result in runoff.

Taking into account all buildings across the state — commercial and residential, in urban and rural environments — Hubbard projects that Wisconsin is facing $2.7 billion of potential building damages, or potential risk from a 100-year flood.

Another recent study by Hubbard shows that a 10 percent increase in rainfall can result in three times as much damage to buildings. This is because rainfall is distributed equally across a watershed and the streams, rivers and lakes moving that water can only funnel so much before flooding, he says.

Armed with information about building locations and the potential financial impact of a flood, the state can help communities to lower, or mitigate, their risk.

This won’t always mean moving the heart of a community’s town to higher ground, but it may mean developing communities with an eye toward greener landscapes that absorb water and building practices that allow for water retention, like rain gardens, rain barrels and other drainage techniques: in general, more pervious landscapes.

Hubbard’s statewide flood report was included in the 2021 State Hazard Mitigation Plan that was developed by Wisconsin to meet Federal Emergency Management Agency requirements on how communities plan for and mitigate natural hazards. Many counties lack the resources to undertake this type of assessment, making Hubbard’s work and collaborations with the state all the more important.

“Wisconsin is lucky because [Wisconsin] Emergency Management is especially good at developing mitigation strategies to address flooding,” says Hubbard. “We are considered one of the leaders in this area.”

This work is supported by Wisconsin Emergency Management and FEMA.

Homepage image credit: Jeff Miller / UW-Madison