Irresistible force meets immoveable object

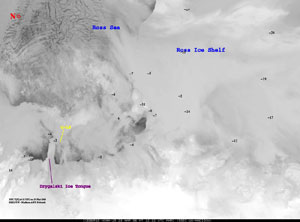

Iceberg C-16 is poised to crash into the Drygalski Ice Tongue. Satellite images prodcuced at UW-Madison’s Antarctic Meteorlogical Research Center help track the movement of the icebergs.

MADISON — During the week of March 20, iceberg C-16 moved rather quickly for a chunk of ice half the size of Wisconsin’s Dane County. It followed ocean currents along the Ross Ice Shelf northwestward towards the Drygalski Ice Tongue, remnant of the David Glacier. C-16 is portion of a larger iceberg that broke off in 2000, part of a regular calving schedule that helps the ice shelf maintain its size.

Such movements would be lost to glaciologists without satellite imagery. In Wisconsin, meteorologist Shelley Knuth, in the UW-Madison’s Antarctic Meteorological Research Center (AMRC), creates images of icebergs daily, sometimes more often, using satellite data. The center has monitored the large tabular icebergs since the current calving period started in 2000.

The Drygalski Ice Tongue is roughly the size of Rhode Island. Iceberg C-16 is about half the ice tongue’s size. Should the entire tongue break from its hold on the Ross Ice Shelf, it would likely alter the currents along the Scott Coast and in Terra Nova Bay, north of McMurdo Sound, and change the area’s climate, according to meteorologist George Weidner, of the UW-Madison’s Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences. It is not certain whether a broken ice tongue would threaten shipping in McMurdo Sound; that depends on how much of the ice tongue breaks off and where the current takes it.

UW-Madison collaborated with the University of Chicago to install a weather station and other instrumentation including GPS on both iceberg C-16 and the Drygalski Ice Tongue. Instruments like those are located around the continent and provide vital information about Antarctica’s weather. If the ice tongue does break, glaciologists will be able to monitor pressure, temperature and wind changes as it and the iceberg move around, matching those measurements with satellite imagery, and adding to the store of glaciology knowledge.

Glaciologist Douglas MacAyeal, professor in the University of Chicago’s Department of Geophysical Sciences, notes that last year mega-berg B15-A came dangerously close to whacking the Ice Tongue. C-16, about half the size of B-15A, is coming much closer to damaging the ice tongue, with its coastal approach, rather than the nearly head-on approach B-15A took. MacAyeal reminds us that this “shows how unpredictable various elements of the climate system can be.”

Weidner notes that, for C-16 to collide with or break the Ice Tongue, the iceberg would need enough momentum to overcome strong Katabatic winds flowing down the David Glacier that would tend to push C-16 to the east. Katabatic winds blow down a topographic incline such as a hill, mountain or glacier, and are prevalent in Antarctica. The ocean currents along the Scott Coast will also likely be deflected to the east along the Drygalski Ice Tongue.

For now (March 27), C-16 nestles close to the Drygalski Ice Tongue, cushioned from an impact by sea ice. On March 29, it had knocked off the very tip of the tongue.

The AMRC, a unit in the Space Science and Engineering Center, also produces mosaics of Antarctica from satellite data, making them available to researchers and others over the internet. Both AMRC and the AWS receive their funding from the National Science Foundation’s Office of Polar Programs.

Latest iceberg image:http://ice.ssec.wisc.edu/ice_images/icebergs/ross/latest_rossF.JPG

More information on Antarctic research at University of Wisconsin-Madison:http://amrc.ssec.wisc.edu/

###

Direct comments, suggestions and inquiries to Terri Gregory, SSEC’s Public Information Coordinator.

For past features and columns, see SSEC’s News page.